This is the second in our our weekly series of interviews with the Rotman Institute’s postdoctoral fellows. Last week’s interview with Alida Liberman can be found here.

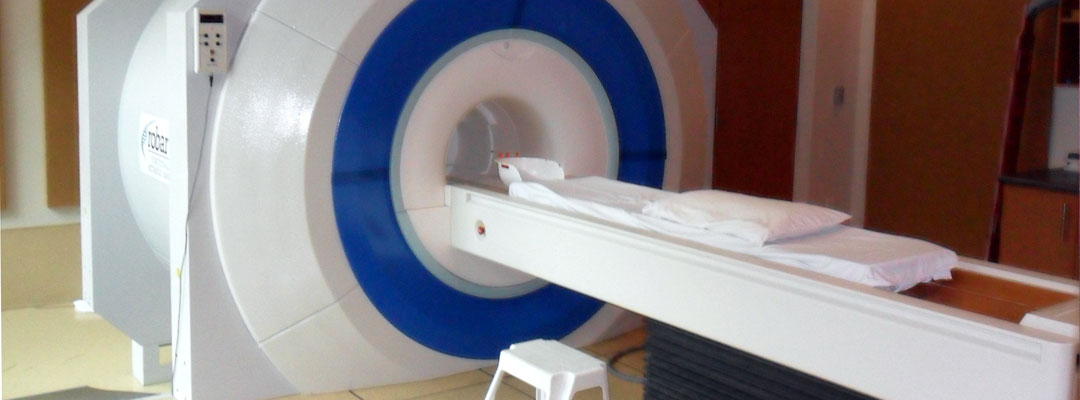

Tommaso Bruni is a postdoctoral fellow at the Rotman Institute of Philosophy in London, Canada. He completed his PhD in 2013 at the University of Geneva in Switzerland. Currently Tommaso works with Professor Charles Weijer and Professor Adrian Owen on ethical issues associated with the use of functional-MRI (fMRI) technology to assess the mental states of patients with disorders of consciousness, including the minimally conscious state, the vegetative state, and coma. His work addresses issues in bioethics, experimental moral psychology, and meta-ethics.

Amy Wuest: What sorts of questions do researchers studying the ethics of neuroscience explore?

Tommaso Bruni: We ask questions like: Is it safe and ethical to run this kind of neuroscientific experiment? What are the rules that should guide neuroscientific research, especially in a clinical context? Under what circumstances can a certain experimental intervention be deployed in clinical practice? How can we best protect research participants without making research grind to a halt? How is clinical research in the critical care context different from clinical research during standard medical care?

AW: What is experimental moral psychology and how does it differ from traditional approaches to bioethics?

TB: Experimental moral psychology is a branch of cognitive science that studies human moral behavior. It asks what happens in the human mind and brain when humans make moral choices, think of moral norms, evaluate others’ actions, and so on. Experimental moral psychology is only loosely related to bioethics, but it could have important consequences for ethics in general. Many theorists (such as neuroscientists, psychologists, and philosophers) have argued that knowing more about how we make moral judgments and morally relevant decisions can help us to be more moral, and to be morally better. I am actually skeptical toward these claims, but there has been a big debate about them over the past few years.

AW: What meta-ethical questions do you explore in your research? Can you provide some examples?

TB: One important issue is the relationship between empirical data and moral judgments. In the late 1700s, Scottish philosopher David Hume famously wrote that it is impossible to directly derive an “ought” from an “is.” To derive an “ought” from an “is,” you actually need a normative premise (i.e., one that indicates what you ought to do) that is usually hidden or kept implicit. In other words, the only valid inference of this kind is:

Premise 1 (often hidden) – ought

Premise 2 – is

Conclusion – ought.

Experimental moral psychology has revamped attempts at deriving moral claims from empirical facts. I think that most of these attempts fail, because they rely on covert normative assumptions that are often controversial and cannot be taken for granted.

For example, experimental psychology showed (see Small & Loewenstein for an example) that we tend to help identifiable victims of a disaster more than larger numbers of anonymous victims. In other words, if we must decide to give $100 to a specific refugee family of 5 members or to a vaccination campaign that helps 50 anonymous children in, say, Uganda, then we will be more likely to give $100 to the family rather than to the campaign. This is a fact, an “is.” Some theorists have argued that we should oppose this tendency, because it creates undesirable outcomes. Our money helps more if it is given to the vaccination campaign. So science, in this case, would have direct normative consequences. However, this normative (“ought”) conclusion depends on an implicit normative premise, i.e. that the only morally relevant consideration is the maximization of the wellbeing of people influenced by our actions. This is a premise that some theorists do not accept: perhaps we should be allowed to make some choices on the basis of sympathy or hunches and not on the basis of utility calculations. For the argument to be sound, the normative premises must be made explicit and defended.

AW: During your time at the Rotman Institute you’ve had the opportunity to collaborate with both Dr. Weijer (the first Director of the Rotman Institute and Canada Research Chair in Bioethics) and Dr. Owen (member of the Brain and Mind Institute at Western and Canada Excellence Research Chair in Cognitive Neuroscience and Imaging). As a part of this collaboration, you’ve studied the ethics of fMRI technology. Can you describe some of this work?

TB: Yes, this is the core of my current work. It all starts with severe brain injury, which may result from anoxia or traumatic brain injury. After severe brain injury, most patients end up in the intensive care unit (ICU). Their main cause of death in that setting is the withdrawal of life-supporting therapy. In other words, they die because the physicians and the family have decided that the prognosis is too poor to warrant further treatment. So, prognosis is key to the survival of these patients. Unfortunately, current prognostication techniques for brain injury, albeit valuable, are imprecise. Functional MRI has considerable promise as a new prognostication technique, but much research is still needed before it can be used in clinical practice. The question we ask is: How can we run this research program in an ethically appropriate way?

AW: In a recent, co-authored publication—“Ethical considerations in functional magnetic resonance imaging research in acutely comatose patients”—six ethical issues related to the use of fMRI technology are outlined. Can you describe one of these issues and explain why researchers and research ethics committees should consider it prior to beginning a study that uses fMRI technology?

TB: One important issue is intra-hospital transport. Moving a patient that is treated in the ICU is not riskless. These patients are very ill, and in order to take them out of the ICU to the MRI scanner you must change their ventilator, expose them to accelerations and decelerations, and keep them lying flat in the scanner for 30-45 minutes. This is associated with a non-negligible level of risk. In the first phases of the functional MRI research trajectory, this risk will not be compensated by any therapeutic benefit. It is therefore essential to minimize this risk. An effective strategy is the use of trained personnel and specific checklists. Then, an additional strategy can be deployed: running the experimental functional MRI scan immediately after (or before) a regular MRI scan that is clinically required by the ICU doctors. In this way there is no added risk to the patient, because she would have gone to the scanner room anyway to have her regular scan. However, scanner time is very valuable and difficult to manage, and doing these dual-purpose scans is not always possible.

AW: How does your earlier research inform this work?

TB: I had previous experience with functional MRI when I was working in P. Vuilleumier’s lab in Geneva. I also read quite a lot about functional MRI methods and functional MRI experiments during my doctoral work. My previous background in bioethics helps too.

AW: Aside from fMRIs, what other technologies do you study?

TB: At the moment, my research focuses on functional MRI, but I’m also interested in electroencephalography (EEG) and in experiments measuring EEG signals in comatose and dying people.

AW: The Rotman Institute of Philosophy strives to engage science. Your work gives us an idea of how science can influence philosophy, so let’s turn this question on its head: What do you think scientists can learn from philosophy?

TB: Scientists are often deeply interested in methodological issues that are of interest to philosophers too. Actually, there is more cross-talk between philosophy and the methodological part of empirical science than one would at first imagine. Philosophy can contribute by clarifying methods and by explaining what can and cannot be concluded from some experimental results. For example, if an experimenter shows scary pictures to participants in a MRI scanner and then finds increased blood flow in a certain area of the brain, are we allowed to call this area “the fear area” or to say that this area is necessary for fear?

In addition, scientists working on human subjects have to work with research ethics boards on nearly a daily basis and are often interested in research ethics. Bioethicists can help scientists to navigate the sometimes perilous waters of protocol reviews and approvals.