by Jamie Shaw

Bill Nye’s recent comments about the (lack of) value of philosophy have caused somewhat of an uproar within the philosophical community. These comments are not new; many scientists and popular figures (including Neil deGrasse Tyson, Stephen Hawking, and Richard Dawkins) have signaled the death of philosophy as a discipline and nominated ‘science’ as its successor. These views are remarkably easy to refute as many have already noted. They are either self-undermining, as they are using philosophy to say philosophy is useless, or simply false as is made readily apparent by the vast array of historical and contemporary case studies of productive philosophical work. It is a question unto itself about why such views persist in popular culture, but it is a more peculiar question about why philosophers, to a certain degree, have internalized this criticism.

One need only glimpse philosophy forums, or overhear a handful of water cooler conversations to know that philosophers often doubt whether their work contributes to society at large. For some areas of philosophy, such as moral or political philosophy, this is an easier doubt to calm than for those in work in, say, speculative metaphysics. Still, when comparing contemporary philosophical achievements to those in the sciences, it isn’t hard to see why philosophers, in spite of their resistance to Bill Nye’s criticisms, sort of agree with the hostility towards philosophy from particular segments of popular culture.

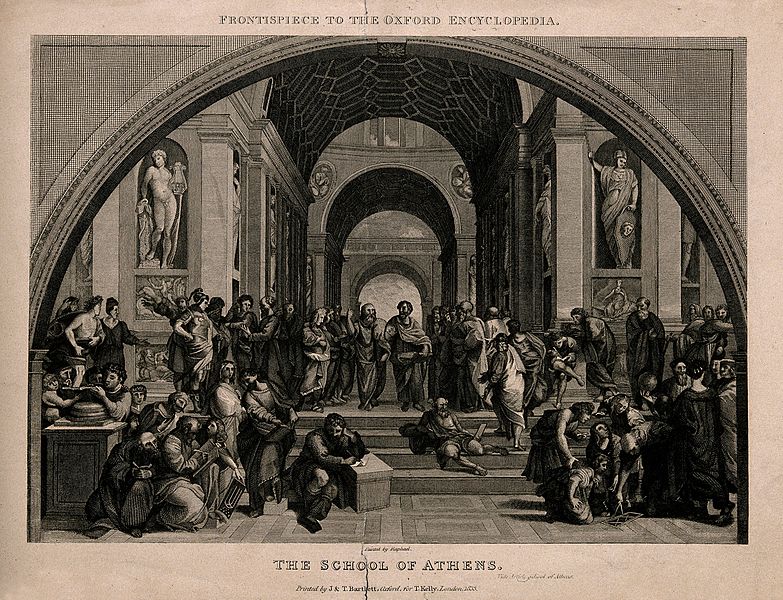

I think there is a reason to be optimistic about our contributions towards society, regardless of which way we do philosophy or which area we work in. Take the example of Leibniz’s monadic theory of time. What could be more highfalutin and obscure? However, some (Muna Staff and Norman Sieroka) have used this view to better understand neurophysiological features of perception. These examples can be proliferated ad nauseum. Just ask yourself the question: where would psychology be today without Kant? Or biology without Hershel? Or literature without Nietzsche? We could also list the greatest scientists of all time, Newton, Darwin, Einstein, Mach and note that they were all philosophers whose philosophy was essential to their scientific contributions. The Renaissance, one of the most important cultural movements in history, began because of renewed interest in Plato and Aristotle! While it may be easy to dismiss highly abstract and seemingly detached philosophical works at first glance as bourgeois ruminations, they have made significant contributions to our current way of living. This is a tradition we carry on today.

Before getting too ahead of ourselves, we should note that the practical import of philosophical work is rarely our first concern. After all, who ends an article on Malebranche’s occasionalism with an upshot about current policy? It would be absurd to expect this much. In fact demanding this would most likely be counterproductive. But it is important, I think, to be reflective of why we do philosophy in the first place. How is it that our work contributes to society at large? Why is it perfectly legitimate that our salaries are paid by tax payer dollars? We have good reasons to think that we have affirmative answers to both of these questions; the task is to remind ourselves of what those answers are.

Pictured above: The School of Athens: a gathering of renaissance figures in the guise of philosophers from antiquity, in an idealized classical interior. Engraving by J. & T. Bartlett, 1835, after Raphael. (courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)