S. Matthew Liao, director of the bioethics program at NYU, recently drew attention to important issues related to the use of propranolol to treat combat related post-traumatic stress disorder. In an interview published in the New York Times, Liao stated that a growing area of interest in the ethics of psychiatric therapy is the use of new drugs that alter traumatic memories:

Right now, the government is quite interested in propranolol. They are testing it on soldiers with post-traumatic stress disorder. The good part is that the drug helps traumatized veterans by removing bad memories causing them such distress. A neuroethicist must ask, ‘Is this good for society, to have warriors have their memories wiped out chemically? Will we get conscienceless soldiers?’

Indeed, the use of propranolol as a standard treatment for PTSD is a growing concern within the ethics community. However, the ethical problems that Liao raises are factually incorrect. To date, there is no evidence that propranolol erases memories, nor does it produce conscienceless soldiers. What it does do is attenuate the “sting” of traumatic memories suffered by the affected patient. In Liao’s defense, this is reviewed in his earlier work published in American Journal of Bioethics (2007).

Notwithstanding these factual details, propranolol still raises several concerns relevant to the study of neuroethics. Given that the current diagnostic model of PTSD is characterized by the central criterion of intrusive recollections (i.e. flashbacks/nightmares), the use of drugs that inhibit neural mechanisms associated with hyper-arousal may be an effective treatment for this population. However, recent studies exploring the relation between dissociative symptomology and chronic exposure to traumatic environments suggest that beta-blockers may not be proper therapeutic interventions in all cases.

It is widely accepted in the neuropsychiatric literature that responses to identical traumatic stimuli can vary within a single patient population. For example, when exposed to an identical combat-related traumatic event, some military personnel have been shown to develop fear-based symptomology, while others do not (cf. Etkin et al. 2007). Such findings have also been replicated in neuroimaging studies where patients satisfying the standard diagnostic criteria of PTSD show heterogeneous neural responses upon exposure to traumatic scripts (Lanius et al. 2010). In some cases, affected patients have even shown opposite neural reactions to the fear-centric model of PTSD. Rather than experiencing hyper-arousal in the face of traumatic stimuli, patients will instead report subjective feelings of depersonalization and derealization. Broadly construed, these symptoms often manifest in the form of “emotional deadness”, or a lost sense of emotional connection to self and environment (Lanius et al., 2010).

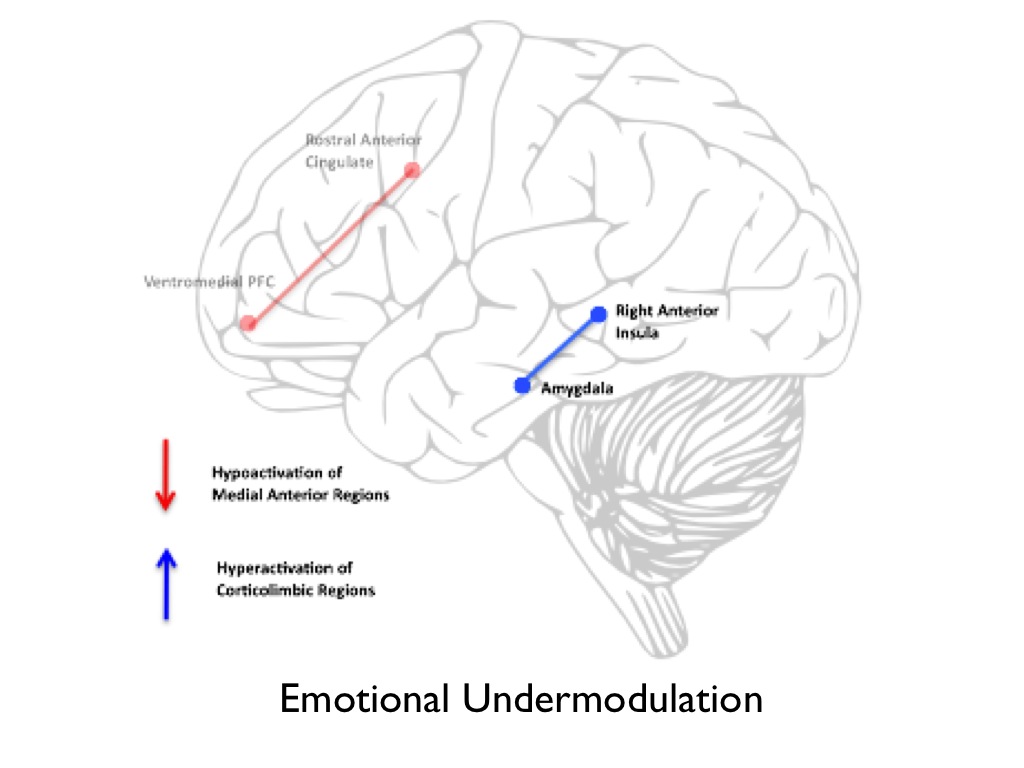

In response to these findings, researchers at Western University have developed a neurophysiological model that explains dissociative symptomology in the context of neural regions standardly implicated in PTSD (Lanius et al., 2010). This model hypothesizes that a complex network between arousal inducing neural regions (the amygdala and right anterior insula), and executive

prefrontal structures (medial prefrontal cortex and rostral anterior cingulate), modulates emotional response to fear-inducing stimuli. In cases of acute exposure to traumatic events, the prefrontal structures responsible for inhibition of corticolimbic regions are hypo-activated. This, in turn, causes clinical presentations consistent with arousal and avoidance. Lanius and colleagues refer to this neural phenomenon as undermodulation of emotional response (see figure 1).

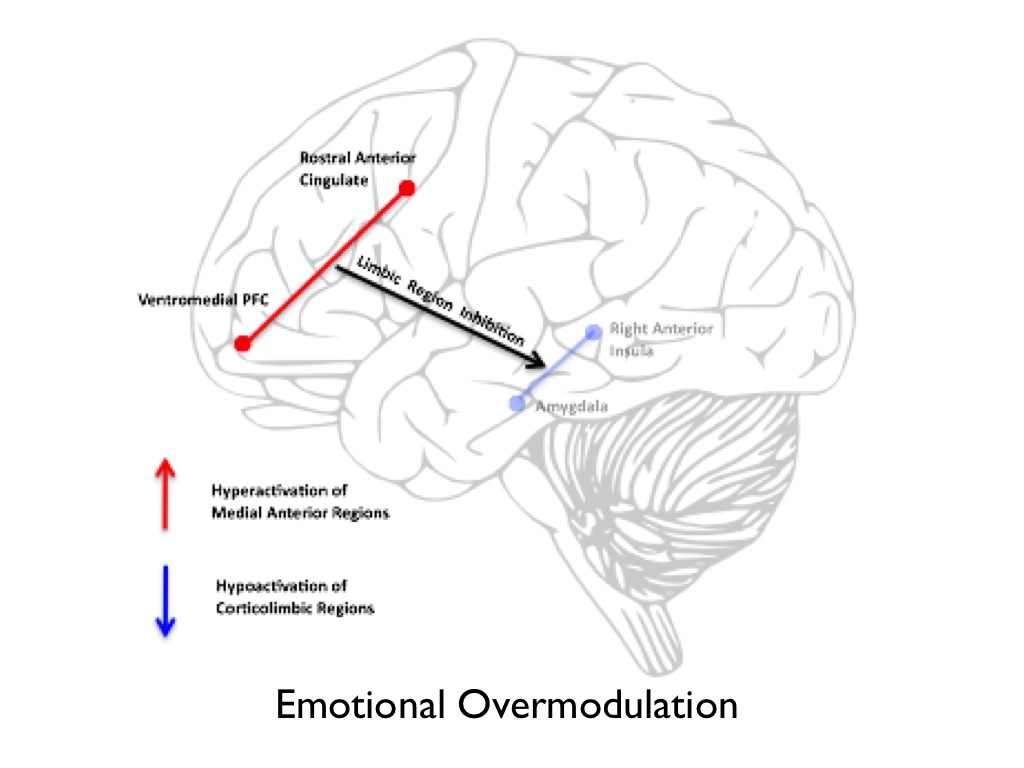

On the other hand, in cases of chronic exposure to traumatic events, inter alia, prefrontal structures are hyper-activated. This, in turn, inhibits arousal inducing brain regions, which facilitates a clinical presentation that fluctuates between hyper-arousal and dissociative symptomology (e.g. depersonalization and derealization). Lanius and colleagues refer to this neural phenomenon as overmodulation of emotional response (see figure 2).

Indeed this dissociative subtype of PTSD has been confirmed in several recent epidemiological studies in both veteran and civilian populations. In two recent investigations targeting prevalence in military personnel, dissociative symptomology was highly correlated with PTSD symptom severity and comorbidity of personality disorder (Wolf et al. 2012a; 2012b). Of those who met the current diagnostic criteria for PTSD in the patient sample, 12% displayed clinical presentations consistent with the dissociative subtype (Wolf et al. 2012b). Likewise, a recent study targeting civilians diagnosed with PTSD found 25% of the patient sample was uniquely characterized by high derealization and depersonalization symptoms (Steuwe et al. 2012). Finding such as these have led researchers to advocate for the demarcation of PTSD from anxiety-based disorders in the new DSM-V diagnostic criteria. In doing so, recognition of developmental factors, such as early childhood trauma, which exacerbate reactions to traumatic events later in life, may allow clinicians to develop psychiatric therapies tailored to a patient’s unique clinical profile.

In the face of this research, the ethical landscape appears to be far more complex than Liao’s assessment suggests. While Liao believes that ethicists should be concerned with the potential for “chemically wiped memories” and “conscienceless soldiers,” the ethical problems are instead tied up with epistemic concerns about the empirical verification of a well-circumscribed psychiatric phenomenon. Before we begin to use propranolol in all cases of combat-induced PTSD, it will be important for the neuropsychiatric community to understand precisely what is happening in the affected patient’s brain. If this is not done, then the use of propranolol, which enhances the emotional numbness characteristic of dissociation, may, in fact, compound psychiatric ailments in patients already coping with dissociative symptomology. The ethicist should, therefore, be concerned with the scientific controversy of accurately circumscribing PTSD as a psychiatric illness and the allocation of appropriate therapies, rather than speculating on the far reaching possibility of a military with no memory or conscience.