Continuing our series of physicists talking about why they find philosophy valuable (Part I here), here’s Carlo Rovelli.

The recent dismissive remarks about philosophy by Neil deGrasse Tyson reopen a debate which I think is worthwhile reopening. Neil deGrasse Tyson is not the only one to consider philosophy useless for science. Many of my colleagues in science have the same view, today. But they would be perhaps surprised to find out that many scientists have the opposite view. Among these are names like Einstein, Heisenberg, Bohr, Darwin and Newton, just to name a few. Why do these major scientists, and so many others of lesser stature, consider and still consider philosophy as an extremely useful enterprise in our search for knowledge? In my opinion, because they understood the nature of the scientific enterprise better than Tyson.

There are several reasons for that. First, if we understand science as a technical machine for collecting data and testing theories, then we do not need much philosophy. But science is not just that. It is, foremost, a complex discipline that constantly critically rearranges its own assumptions. When Copernicus put the Earth in motion, when Heisenberg and Einstein question the Newtonian view of reality, and when Feynman proposes a new picture of interacting quantum particles, these scientists are involved in conceptual work which is nourished by philosophy. Heisenberg would have never taken the step he took without the positivism of the 19th century. Einstein would have never questioned the nature of time if he had not read the philosophical questioning of Mach and Poincaré. Newton is inconceivable without Descartes before him. Feynman, with all his effective concrete attitude, would have never been possible without the subterranean influence of the American pragmatism. And so on.

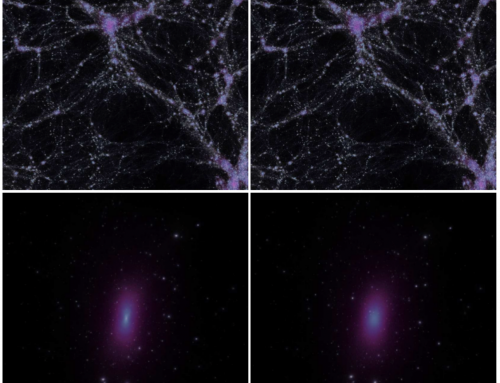

This brings me to the second reason that stating that science is independent from philosophy is a naive position: the scientists who claim that do without philosophy are not really without philosophy; they hold a philosophical position without thinking and without being critical about it. This is particularly visible in my own discipline, theoretical physics, where I think that the influence of philosophy, often badly digested, has been far wider than recognised: the ideas of Popper and Kuhn have become the credo of contemporary theoretical physics. Some of these ideas are of course very good, but the uncritical acceptance of these ideas as god-given truth has led a substantial part of the discipline out of course. In particular, a reading (perhaps naive) of these philosophers, who undervalue the reliability of the qualitative content of empirical successful theories in searching for more effective extensions of these theories, has led contemporary theoretical physics into a rather sterile exploration of all sort of possible alternative theories, with the only justification being to try this and that. This is an attitude that historically has never paid. Thus, lack of philosophical awareness, belief that the “rules of science” are clear, god-given and do not need discussion, is a superficial attitude that can cause damage to our scientific knowledge.

Dismissing philosophy as useless is as naive as the attitude, common today in many corners of the world, as dismissing science as “not true knowledge.” Of course there is also bad philosophy, as there is bad science. But what we understand today about the world, ourselves, our culture, our own very process of acquiring knowledge, is a complex web, which is rich and effective if taken in its entirety. To my colleagues in science who dismiss philosophy, I say: think better, recall what Einstein did, taking ideas even from Spinoza and Schopenhauer. Are you sure you are smarter than him?