Here’s the latest in our series of physicists writing about the value of philosophy: Ivette Fuentes on the interplay between science and philosophy (and also science and the arts!)

Science and philosophy share common goals. They aim at developing and deepening our understanding of reality, at uncovering the basic constituents of the Universe and its fundamental laws. Science and philosophy also share a common past. In the early modern period the words “science” and “philosophy of nature” were used interchangeably. Science was born from natural philosophy. But the overlap between science and philosophy is not only a matter of the past. In our present search for knowledge there are many moments in which the lines between them blur. Every single scientific theory and philosophical exploration starts with questions and with reflection upon them. Basic ideas are produced in order to provide answers to these questions. These ideas are developed though critical and logical thinking. At this point science and philosophy are indistinguishable. Then comes the moment in which methods are applied to formalise the questions and the ideas to provide their answers. The methods in science and philosophy differ. Science generates knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions. Physics, for example, heavily relies on mathematics to make these predictions. Philosophy relies on rational argument. During this time science and philosophy become distinguishable; however, they merge again at later times. Once a new scientific theory is proposed, it is not only confronted with experiments (when possible) but also to philosophical scrutiny. Once a theory is born, there is an unavoidable need to interpret the objects of the theory and its results. At this stage science and philosophy again come close together. In the early days of quantum mechanics philosophical discussions played a central role. The founding fathers of the theory had to give meaning to mathematical objects, for example, the wave function.

In my opinion a scientist who is not open to exploring that zone where science and philosophy overlap is missing out on the opportunity of taking his or her science to the point where truly new ideas are developed. Lately I been having very interesting discussions with philosophers. These discussions made me very aware of all those assumptions we physicists usually forget about in order to make progress in our work. For example, I’ve been talking to Jonathan Tallant and Stephen Mumford about the nature of time. Most physicists use the notion of time every day to calculate, however, we rarely stop to think about what time is. And does it matter? Well, it depends. If one aims at producing incremental knowledge, probably not. If one is restricted to work within a given paradigm, then perhaps philosophy is not necessary. Once a theory is established, because it succeeded at predicting the outcomes of experiments, or because enough people were convinced to work on it, it becomes much less common that scientists become preoccupied with philosophical questions. This is perhaps necessary in order to make progress within a theory. This is when the shut-up and calculate or don’t-think and calculate style of working adopted by some scientists provides efficiency at finding results. However, if the theory fails at explaining parts of reality, then it becomes necessary to reflect on the assumptions made, to re-interpret, to think deeper. And we must enter that grey area between science and philosophy because the shut-up and calculate approach fails. This approach is no longer efficient when evidence points out for the need of a more fundamental theory of nature. When one is after something new, deeper questions are always essential. New perspectives require questioning the very fundamental elements of a theory, becoming aware of all the basic assumptions. It also requires creative thinking, inspiration, connecting dots, integrating. In my experience, interacting with philosophers and asking questions which some physicists would consider forbidden has helped me come up with new ideas. When considering philosophical questions, I often find myself thinking harder and understanding better my own work. The point of view of philosophers often provides different perspectives to my own. In my case, these new perspectives inspire me to come up with new ideas. Some of these ideas have lead to new results that are now being tested in the experiment. From a discussion with Jonathan, I became interested in understanding how quantum laws limit the capacity of clocks to measure time. Quantum metrology tells us that quantum clocks are the most precise clocks. I wanted to understand how the uncertainty principle sets fundamental limits on how well we can measure time. To approach this question we developed a model for a quantum clock moving in space-time and Per Delsing’s group at Chalmers University is implementing the clock in their laboratory. Our work lead to a new result, we found that particle creation (a genuine quantum effect) affects time dilation slowing down the clock.

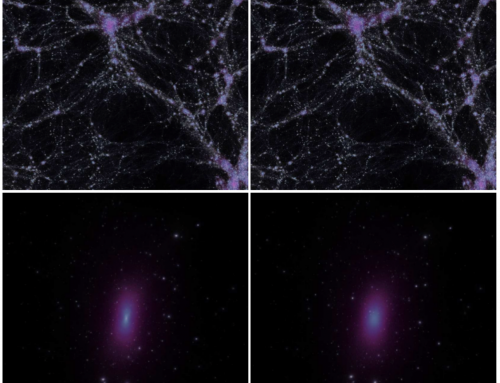

Many scientists, surprisingly, think that new concepts are unnecessary. One just needs to look into the overlap of quantum mechanics and relativity to see how wrong this is. Quantum theory and general relativity are the most fundamental theories we know of nature. They are both established theories that succeed at describing experiments in their respective regimes of applicability. Quantum theory describes the physics of very small length scales, while general relativity succeeds at explaining phenomena at the large scales. If one works in either theory, one might not feel the need to establish a dialog with philosophy. One might prefer to invest time in developing technical tools to approach complicated problems. However, experiments in quantum mechanics are now reaching regimes where relativity kicks in. These include experiments that aim at distributing quantum entanglement between links in Earth and satellites. But quantum mechanics and relativity are incompatible! How are we going to understand the outcomes of these experiments? Take again time as an example. General relativity states that space and time are one and the same thing. In GR there is no absolute time. Einstein phrased this as: “People like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion”. However, in quantum theory space and time are treated differently. Time is an absolute parameter while the position in space of quantum particles can be undetermined due to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. In general relativity time can flow at a different rate in different regions in space, while in quantum theory, spacelike separated particles can be entangled at the same time. We have not understood well how these effects overlap. In order to attempt to provide answers, it is necessary to consider philosophical questions such as what are space and time. And here science and philosophy must work together. Jonathan, Stephen and I have a project in which we propose to explore time not only through science but also through the arts and their interaction. Our society usually regards arts and sciences as being separate disciplines, somehow also incompatible. Art is usually identified with creativity and science with logical thinking. Most people are unaware of the profound creative thinking required in science. And it’s hard to be creative when one unnecessarily limits oneself to applying techniques or to thinking within an established framework. We do not know where creative thought comes from, it is a mystery. I believe that being open to different views, different ideas, different ways of doing things is a key to creativity. Art and Science are both creative at their roots, and in a sense they are one and the same thing, in spite of their methods being different. The separation between them is perhaps also only another stubbornly persistent illusion. The interplay between arts and science might provide new insights that are only possible through the interaction of both disciplines.